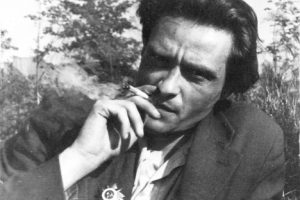

February 18th 2024 marked the centenary of the birth of Evald Ilyenkov (1924–1979) – a brilliant and influential Soviet philosopher whose most important early works remained unpublished during his lifetime (fig. 1). Two days before Ilyenkov’s 100th birthday, Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny was found dead in a Siberian prison colony; that news overshadowed the little attention given to Ilyenkov’s anniversary in Russia. The manner in which Ilyenkov’s centenary and Navalny’s death were treated reflects memory culture in Putin’s Russia, where the legacies of Soviet Marxism are often suppressed by ultra-nationalist propaganda. Abroad, Ilyenkov’s prestige has seen a remarkable rise in recent years, accompanied by translations and new scholarship in, for example, Sweden, Ukraine, Peru, Turkey, Canada and Cuba.

On his 100th birthday, Ilyenkov continues to shape Marxist philosophy, radical pedagogy and psychology around the world. His philosophical interests included political economy, logic, cybernetics, science fiction, epistemology and aesthetics. His radical fusion of Spinoza, Hegel and Marx transformed Soviet intellectual life from the 1950s to the 1970s. Best known for his analysis of Marx’s dialectical method, he reinvented the study of materialist dialectics in the Soviet Union. The Dialectics of the Abstract and the Concrete in Marx’s Capital (1960) made him famous both at home and abroad. Swiftly translated into Italian, Spanish, German and English, his succinct reading of Marx’s Capital significantly influenced Italian and Latin American leftist thought.

Ilyenkov’s philosophy emphasizes the importance of connecting philosophy, pedagogy and psychology to promote the emancipation of the individual. Various notions, among them the idea of tacit knowledge, are very much indebted to him. His warnings against the dangers posed by quantification measures, artificial intelligence and unrestrained capital accumulation amount to a socialist humanism that has great relevance today.

Born in Smolensk, Ilyenkov grew up in Moscow. His mother was the teacher Yelizaveta Ilyinichna (Ilyenkova), his father the novelist Vasily Ilyenkov (1897–1967). The family lived in a commune house, a progressive form of early Soviet housing popular with the intelligentsia. Shortly before the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Ilyenkov began studying philosophy at the famous Moscow Institute of History, Philosophy and Literature (IFLI). There, his teacher Boris Chernyshev (1896–1944) sparked Ilyenkov’s interest in classical German philosophy. An expert in Greek philosophy, Chernyshev also introduced him to the history and study of dialectics, which he considered essential for forming philosophical arguments.

In Moscow, during the height of Soviet war propaganda against fascism and German culture, Ilyenkov read Hegel and listened to Wagner. In 1942, being drafted into the Red Army, he interrupted his studies. He marched to Berlin as an artillery lieutenant with his camera, and photographs from that time show him posing in uniform. At Dorotheenstadt cemetery, he visited the graves of Hegel and Fichte. Upon his return to the Soviet Union in 1946, he continued his studies at the Faculty of Philosophy in Moscow, graduating with honours in 1950.

Communist Cosmology

The late 1950s saw a renaissance of philosophy in the Soviet Union. Previously banned thinkers and ideas briefly gained popularity. Hegel and the Romantics weere now seen as forerunners of Marxism-Leninism. Ilyenkov organized a private reading group in his apartment to discuss Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, which had just been published in Russian. Still, despite de-Stalinization, he was unable to publish his first philosophical works. In Notes on Wagner (Zametki o Vagnere), published posthumously, Ilyenkov interprets Wagner as a radical socialist and a Romantic counter-figure to Marx, detecting in his music traces of an anti-capitalist cosmology.[1]

Ilyenkov’s most important text, Cosmology of the Spirit (Kosmologiia dukha), also remained unpublished during his life. Drawing on Engels’s Dialectics of Nature, Ilyenkov argues that in communism, the act of thinking materially manifests itself as a cosmic event – a crucial stage in the circular evolution of the solar system which, according to the laws of thermodynamics, can only end in thermal death. To defy the law of entropy in the solar system, he suggested that humanity would commit collective suicide, as “a gesture of self-destruction on the part of communist reason.”[2]

According to Ilyenkov, matter gains consciousness in certain parts of the universe. The “thinking brain appears as one of the necessary links, locking together the universal [vseobshchee] big circle of universal [mirovoi] matter.”[3] Cosmology of the Spirit draws on scientific theories and innovations, such as thermodynamics, the Soviet space program and the construction of the first nuclear power plant near Moscow in 1954. It is a reflection on technology and materialism and was Ilyenkov’s first attempt to develop a theory that can avoid both crude materialism and idealism.

Philosophy as the Science of Thinking

Ilyenkov’s official career had begun in 1953 when he completed his thesis on Marx’s materialist dialectics. He soon became a popular lecturer in philosophy. After Stalin’s death in 1952, philosophy in the Soviet Union shifted towards scientification, circumvening political or ideological questions. In 1954, Ilyenkov and Valentin Korovikov (1924–2010) were commissioned to write a paper on the status of philosophy. They argued that the categories of logic are the forms in which human practice embodies scientific knowledge, and that their historical development belongs to the domain of philosophy. Philosophy is therefore not a meta-science, but, they claimed, rather the science of thinking, analyzing its general laws and historical development. For Ilyenkov and Korovikov, this renewal of philosophy would need to be accompanied by a transformation of the entire system of science. Each scientific discipline would have to develop its subject matter and methodology without the interference of other scientific disciplines. Philosophy’s task would be to generalize and interpret the results of the natural sciences, devoting itself to each science with its own categories and concepts. Their 15 Theses provoked fierce resistance among the philosophical establishment. After a general meeting at the Faculty of Philosophy of Moscow’s State University in the spring of 1955, during which Ilyenkov and Korovikov clashed with members of the conservative establishment, a decision was taken to ban both scholars from teaching. While Korovikov left academia and became a successful journalist for Pravda in Africa, Ilyenkov took up a position at the Philosophical Institute of the Academy of Sciences. There he was supported by Bonifaty Kedrov (1903–1985), who had been one of the founders and the first editor-in-chief of Voprosy Filosofii [Problems of Philosophy], the leading philosophy journal in the Soviet Union.

The Ideal in Dialectical Materialism

Having posited philosophy as the science of thinking, Ilyenkov sought to further develop Marxist epistemology. Of course, the very notion of thinking poses a challenge for every materialism, including dialectical materialism. It asks whether thought is just a function of the material brain best explained by physiology. Popular theories by the physician and physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) led many philosophers to believe that physiology would provide all the answers. Ilyenkov strongly opposed the view that thinking could be reduced to a measurable product of the brain. Instead, he insisted that only philosophy would be up to the task of understanding what thought and thinking are. He therefore introduced the concept of “the ideal” into Soviet Marxist philosophy, arguing that philosophy should attempt to explain in on a material basis. The ideal is the idea that the foundation of thinking should be sought in the historical development and social practices of humans, rather than in their biological makeup. In 1962, in an important article in the Soviet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Ilyenkov explained his position:

“The ideal is not an individual-psychological, even less a physiological fact, but a social-historical fact […] realized in the manifold forms of social consciousness and the will of the human being as a subject of the social production of material and spiritual life.”[4]

For Ilyenkov, the ideal encompasses feeling, thinking and the psyche, but also culture and theory. According to him, all these phenomena possess a special kind of objectivity, distinct from that of physical-material matter. The ideal, he suggests, exists independently of any particular individual human being. However, it depends on humanity’s material reproduction processes. The ideal is essentially the social interactivity of all people. It assumes form as a relationship between material things, processes and events, whereby an object remains what it is while simultaneously representing another object, just as a coin remains a coin but at the same time functions as a means of payment in society, thus representing a social relationship.

Ilyenkov opposed attempts to limit the ideal to the psyche or to locate it within the brain. He defends this view in the sci-fi parable On Idols and Ideals (1968), an intense critique of cybernetics, automation and artificial intelligence. From the mid-1950s onwards, cybernetics had been discussed in the Soviet Union as a potential break-through in overcoming economic and social stagnation. Ilyenkov was sceptical of such visions of “machine communism” and insisted that human thinking possessed unique strengths.

According to Ilyenkov, a conscious human being is not a thinking machine. He or she is an embodied, social being with different organs of thinking: brain, hands, and eyes. What distinguishes a human being from a machine is its ability to deal with contradictions and to comprehend alterity. Whereas a machine can only process information according to its own logic “through rubber-stamped actions encoded into the hand or mind,”[5] humans have the ability to interact with many things that are not themselves. To create artificial intelligence, Ilyenkov argues, it is not enough to create a “model brain.” The brain on its own is as incapable of thinking as legs removed from the body are of walking. Organs can only work when connected to what Ilyenkov, with reference to Spinoza, calls a “thinking body.” This body is not necessarily an individual’s body, but rather the totality of social activity.

The Zagorsk Experiment

The idea that the foundation of thinking should be sought in the historical development and social practices of humans, rather than in their biological makeup, is referred to as the “ideal.” The concept of the ideal can be explained with reference to the sensory activity of “thinking bodies” in space and in their interactions with others. This position was not a central belief to Soviet Marxism because it defied experimental verification, but Ilyenkov found like-minded thinkers within cultural-historical psychology, such as Alexander Luria (1902–1977) and Alexei Leontiev (1903–1979), who also wanted to break the dominance of physiology in this matter. His closest ally at the time was the psychologist Alexander Meshcheriakov (1923–1974), temporarily a colleague of Luria, who headed the laboratory for deaf-blind education at the Institute of Defectology in Moscow. Later on, Mescheriakov headed a school for blind and deaf children that was located in Zagorsk (today Sergiyev Posad) in the suburbs of Moscow. Known as the “Zagorsk Experiment,” the innovative education of deaf-blind people under his aegis made history. After Meshcheriakov’s death in 1974, Ilyenkov continued his work until his suicide in 1979 (fig. 2).

While Meshcheriakov primarily tried to clarify what distinguished deaf-blind people from those who can see and hear, Ilyenkov was more interested in exploring where the human mind begins and how it works. With his work, he challenged Western Enlightenment’s idea that the mind forms a self-contained, interior world accessible only through language. Meshcheriakov and Ilyenkov’s work with deaf-blind children suggested that learning to speak through tactile sign language is a social, embodied process that cannot be reduced to an individual’s acquisition of language. The development of the mind begins when a child engages in an elementary activity, such as initiating a coordinated movement in space. If the child is deaf-blind from birth, and if unassisted, they cannot satisfy its need to eat. Through interactions with parents or teacher, a child learns the actions they require to satisfy their basic needs. In the case of learning to use a spoon a child has to adapt their hand movements to the shape of the spoon and learn the necessary physical motions. Initially, they resist this motion because they do not know that a spoon can be used to eat soup. Only with practice is a mark left on the child’s thinking body. Ilyenkov drew a provocative conclusion from his work in Zagorsk. All expressions of the human mind are socially determined:

“The whole of the human mind (all 100 percent of it and not 80 percent or even 99 percent) emerges and develops as a function of the work of the hand in an external space filled with such objects as a spoon, a potty, a towel, a pair of pants, socks, tables and chairs, boots, stairs, windowpanes, and so on. The brain is merely the natural material that turns into an organ of specifically human life activity and the mind only as a result of the actively formative influence of active work by external organs of the body in an external space filled not with natural but with artificially created things.”[6]

Some of Ilyenkov’s pupils at Zargosk went on to graduate from the Faculty of Psychology at Moscow University, such as Alexander Suvorov, who earned a doctorate in psychology. Could it be said that such success stories proved correct the ideas of Ilyenkov and his colleagues? His critics thought not, and the Zagorsk Experiment was heavily criticized from the start. It was argued that being deaf-blind automatically limits a child’s development. By contrast, Ilyenkov’s inclusive, anti-ableist vision for the human being pointed to what was achievable in a socialist society.

On his 100th anniversary, Ilyenkov may teach us that philosophy, psychology and pedagogy are not three different disciplines but one science dedicated to the same ideal: the development of human personalities, in harmony with their environment and with each other.

Isabel Jacobs is a PhD student in Comparative Literature at Queen Mary University of London, Martin Küpper is a PhD student at Kiel University and doctorand at the project “Philosophy in Late Socialist Europe: Theoretical Practices in the Face of Polycrisis” at Babeș-Bolyai University. Together with Zaal Andronikashvili and Matthias Schwartz (both ZfL), they organize the International Conference Images of the Ideal. Evald Ilyenkov at 100, taking place at the ZfL from the 15th to the 17th of May 2024.

[1] Evald Ilyenkov: “Notes on Wagner,” translated by Isabel Jacobs, in: Studies in East European Thought (2024).

[2] Alexei Penzin: “Contingency and Necessity in Evald Ilyenkov’s Communist Cosmology,” in: e-flux Journal 88 (February 2018).

[3] Evald Ilyenkov: “Cosmology of the Spirit,” in: Stasis 5.2 (2017), 164–190.

[4] Evald Ilyenkov: “Ideal’noe” [1962], translated by Isabel Jacobs, in: Kul’turno-istoricheskaia Psikhologia 2 (2006), 18.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Evald Ilyenkov: “A Contribution to a Conversation About Meshcheriakov” (1975), in: Journal of Russian and East European Psychology 45.4 (2007), 85–94, p. 93.

VORGESCHLAGENE ZITIERWEISE: Isabel Jacobs/Martin Küpper: Philosopher of the Ideal: Evald Ilyenkov at 100, in: ZfL Blog, 8.5.2024, [https://www.zflprojekte.de/zfl-blog/2024/05/08/isabel-jacobs-martin-kuepper-philosopher-of-the-ideal-evald-ilyenkov-at-100/].

DOI: https://doi.org/10.13151/zfl-blog/20240508-01