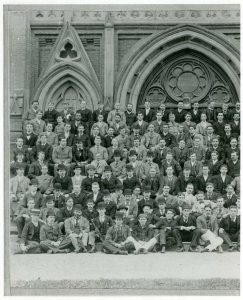

A picture from the late nineteenth century showing about one-hundred students (fig. 1) – all of them male and similarly dressed in suits and neckties, some of them wearing hats. They display a degree of homogeneity unusual by today’s standards. An attentive observer will nonetheless detect that one of the students differs from his colleagues: he has significantly darker skin. The young man, seated in the second row from the top, is the African-American W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963), who was enrolled at the University of Berlin from 1892 to 1894.[1] When, in the hopefully not too distant future, the bustling university life resumes, when students cram into crowded lecture halls again, push through full corridors, past perhaps intimidating, perhaps inspiring sculptures, portraits, and other visual reminders of the apparently glorious past their alma mater is connected to, students of the Humboldt University will come across a memorial for Du Bois, one of the first American sociologists, co-founder of Pan-Africanism, civil rights activist, and prolific author of books such as The Souls of Black Folk (1903).

Particularly in the light of the ongoing debate about structural racism in Germany, it may seem surprising that Du Bois spoke in exceptionally positive terms about his experiences at a German university. He was, after all, enrolled in Berlin shortly after the Congo Conference (1884–1885) and attended the lectures of controversial figures such as the nationalist and anti-Semite Heinrich von Treitschke.[2] The several occasions on which he later returned to the city include an extended sojourn to fascist Berlin in 1936, the year of the infamous summer Olympics, and a visit to communist Berlin, when he was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Economics in 1958. In his last autobiography written a few years before his death, he commented on his student years:

Of greatest importance was the opportunity which my Wanderjahre in Europe gave of looking at the world as a man and not simply from a narrow racial and provincial outlook. This was primarily the result not so much of my study, as of my human companionship, unveiled by the accident of color. […] From this unhampered social intermingling with Europeans of education and manners, I emerged from the extremes of my racial provincialism. I became more human; learned the place in life of “Wine, Women, and Song”; I ceased to hate or suspect people simply because they belonged to one race or color; and above all I began to understand the real meaning of scientific research […].[3]

In a time when ‘internationalization’ and ‘diversity’ have become key areas universities are expected to excel in, it may seem an almost self-evident endeavor to install a memorial for a figure as influential and internationalist as Du Bois, whose connection to the Humboldt University outlasted two ideologically very different political systems. Planned to be positioned in the ground floor of the main building, the memorial, which will start production as soon as the last funding has been secured, reveals an image right at its center that “exist[s] in virtually every student’s life and family album, and commonly serve[s] as vehicle[s] of recognition, remembrance and commemoration”: the class photograph.[4] What are the main considerations underlying the W. E. B. Du Bois Memorial’s concept and design? How has it evolved so far? And what can such a memorial realistically achieve?

As Du Bois’s experiences in Germany – and their effects not only on his own writings but on African-American and Black diasporic literature in general – are highly relevant to my research on the “Images of Germany and German History in African-American Literature,” it was of great interest to me to discuss these questions with two of the creative minds behind the memorial: the Berlin-based Afro-Caribbean conceptual and visual artist Jean-Ulrick Désert, who was entrusted with its realization, and Dr. Dorothea Löbbermann, faculty member of the American Studies Program at the Humboldt University. Due to the current circumstances, I originally conducted separate conversations with each of them digitally, which were later edited to the present form. I wish to thank both of them for their participation and their feedback on the original manuscript!

Gianna Zocco

Gianna Zocco: Dorothea, the American Studies Program at Humboldt University honors Du Bois’s legacy with two lecture series, the “W. E. B. Du Bois Lectures” and the “Distinguished W. E. B. Du Bois Lectures,” which were both established in 1998. What was the reason for you to take the initiative of commissioning a memorial, and what is the current state of the project?

Dorothea Löbbermann: Anecdotally, I ran into a group of Black American tourists who were searching the university’s main building for “the W. E. B. Du Bois statue” of which they had read in a guide. All I could do was take them to the second floor of the building and show them the Du Bois portrait we had once ordered from a poster website. It was embarrassing to see them take selfies in front of that cheap frame, hanging amongst our semester announcements. That’s how the idea for a plaque commemorating Du Bois’s student years at Humboldt University was born. We knew that we did not want a simple plaque and so asked Jean-Ulrick, with whom we have had a long creative relationship, to design a somewhat more expressive, or rather explorative, piece. After the first few drafts, it became clear that the word plaque would no longer fit. As a site, we found a niche next to the university’s International Club “Orbis Humboldtianus,” which we think is very fitting for a memorial to a former international student. We talked to the university’s technical department and to the president, all of whom were extremely supportive, and started raising funds. So far, we have received amazing sponsorship from mainly US American sources (institutions and individuals); we need to be more successful with German institutions. With about 5.000 Euros that we still need to acquire, and with the corona virus dominating the university’s activities, we have not yet been able to enter the production phase of the memorial.

GZ: Jean-Ulrick, in the brief video available on the website of the university that shows the development of the memorial, one can see that the large image at the center is a class photograph. It shows Du Bois and his class at Humboldt University from presumably 1894 and is flanked by two portraits on the left and right. Why did you choose the class photograph as central image of the memorial?

Jean-Ulrick Désert: In my research for the memorial, I went through hundreds of archival photographs, but when I found this class photo, I had no doubt that it needed to be the central image of the memorial. On the one hand, a class photograph is something everyone can relate to, perhaps sometimes with horror but mostly also with some affection and nostalgia. It is a format you can find in Europe, America, on the African continent, even in the Caribbean, where I’m from. In my work as an artist, I like to employ elements with a certain familiarity, even banality, which – when you use them in a certain way – can have a special power. This brings me to another goal I had for the memorial: I was always interested in somehow touching the nineteenth century, in reaching back to Du Bois’s time in Germany while not avoiding the 21st century altogether, either. The technique we’re using with the class photograph would have been impossible even fifty years ago: We are taking the digital image of the class photograph and are connecting the computer with a laser machine, which will then very accurately etch the image into stone. The use of direct materials such as real stone – a black marble or black stone – for the class photograph, and thick glass, polished brass, and white marble for other elements of the memorial, is in itself reminiscent of the aesthetics of the nineteenth century. Moreover, the black-on-black image of the class photograph develops this complicated, difficult quality of seeing that we know from nineteenth century daguerreotypes: You have to look, really look, and then there is this one moment of magic, because you have to put your head in the right focal point to see, back into the past if you will, with special focus and concentration.

GZ: Left and right from the class photograph, you plan to position two portraits of Du Bois. One of them shows him as a young person, and the other as an older man. The latter is a very well-known image of him from later life, when he had already become the distinguished “elder statesman”[5] of not only the Harlem Renaissance but also the American civil rights movement and Pan-Africanism. On the video, I saw that you plan to put these images behind glass in – at least for a memorial – surprisingly bright colors: red and green. What were your thoughts behind this?

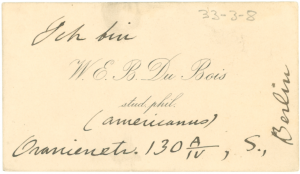

JUD: I was attracted to the idea of this kind of double portrait, because I did not want to show only the iconic image of how he is probably remembered by most people. Again, I found it important to confront the students with someone their own age, of giving them this hopefully very positive, inspiring idea that they are in the moment of their own genius, that they can do meaningful work in their twenties and don’t have to wait until they reach old age. Then there was the question of how to express this not only with beauty, but also with symbolism. I wanted to relate the project as closely as possible to Du Bois as he was in Berlin, to this period in his life that he later called his “Lehrjahre.” The most direct link to the man himself is his signature on the very top, which will be cut out of a golden brass panel so that it is literally turned into air – a very minimalist way of creating a presence of someone who is absent. The signature reflects his own handwriting in the 1890s. I found those visiting cards with his name and notes on how to introduce himself in German (fig. 2), so I wanted to really inscribe his own hand in the work.

Another important anchor was the year 1900, still fairly close to his student years in Germany: 1900 is not only the year of the first Pan-African conference in London, where Du Bois gave a speech titled “To The Nations of the World,”[6] but also the date of the 1900 Paris Exposition, where he helped to install “The Exhibit of American Negroes.” The coloring of the images discreetly alludes to the colors of the Pan-African flag with its three bands in red, black, and green. The flag has a very complicated history and was altered several times, but what remained constant was, significantly, the black in the center. For the red and the green there is more flexibility, and I tried to create a little bit of a feeling of these colors while avoiding kitsch or a cartoonish appearance.

GZ: The years around 1900 were when Du Bois was an aspiring scholar, when he was most dedicated to combating racism through empirical work in sociology. In 1895, one year after his return from Germany, he became the first African-American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University. And shortly after that, in 1897, he began a professorship in the American South, at the historically Black Atlanta University in Georgia, where he taught until leaving academia for a job with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. It was here that he worked on his contribution to the Paris exhibition,[7] which included not only a set of detailed charts, maps, and graphs on aspects such as the economic power and literacy among African-Americans in Georgia but also a series of photographs, which his biographer David Levering Lewis aptly described as subverting “conventional perceptions of the American Negro by presenting to the patronizing curiosity of white spectators a racial universe that was the mirror image of their own, uncomprehending, oppressive white world.”[8] How did the exhibit at the World Fair in Paris inspire your design for the monument?

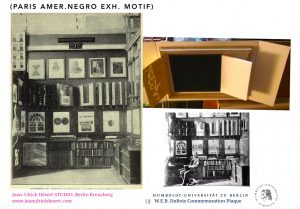

JUD: There are several subtle references that relate to the visuality of the exhibit in Paris. One reference point is the elaborate system of pivoting panels that Du Bois and his students constructed for the exhibit specimens, which enabled visitors to absorb a lot of content quickly and decide what to focus on in more detail. This inspired the arrangement of the different elements of the memorial, which emulates Du Bois’s inventively practical system rotated 90 degrees (fig. 3). Another element that I found interesting about the maps and graphics related to Du Bois’s sociological studies is the use of very bright colors. This made me think that we should not be too shy about colors ourselves and that we could afford to, yes, bring in the gold, and the red, and the green, and liberate us from the typical model of the dark bronze plaque that one finds ubiquitously for such commemoratives.

GZ: In these different stages of developing the memorial, how was the collaboration with the colleagues from the American Studies Program?

DL: The team directly involved with the memorial consists of professors, academic staff, and Ph.D. students; it is in constant conversation with the other American Studies colleagues, and has also received support from the rest of the Department of English and American Studies. We have organized two small events to discuss and contextualize the memorial; the first in the year of Du Bois’s 150th anniversary, where we invited five wonderful students from the historically Black Albany State University, Georgia, as well as scholars and activists of color from Berlin (“The Legacy of W. E. B. Du Bois: Interdisciplinary Responses,” October 2018). In October 2019, we met under the title “Traveling Ideologies: W. E. B. Du Bois in Germany, the USSR, and the People’s Republic of China.” Jean-Ulrick participated in both events, providing the artist’s perspective on the memory of Du Bois. I am convinced that artists, scholars, and activists should foster interdisciplinary exchange and share questions, visions, and methods they apply for their work.

JUD: Right from the beginning of working on the memorial, I felt the weight of a certain responsibility, because I knew of Du Bois as a very complex, immensely productive intellectual and activist, whose work some scholars spend their lives studying. I was aware that I could not fulfill the many roles required. So, I felt that this was not the type of project that would just come out of my own studio, but that it needed multiple collaborative engagements – with a local graphic designer, someone to help me with the research and production, and, most of all, with the American Studies Program because, ultimately, this reflects an aspect of their research mission. I’m an artistic bridge with a particular kind of knowledge and an ability to engage with symbols and forms, but I ultimately desire the American Studies Program of Humboldt University to fully embrace the memorial and to be in shared agreement with its emerging logic. I can definitely confirm that it grew more refined through our many discussions. For example, the original design was a timeline, which certainly has some advantages like a great deal of flexibility. The current scheme with its origins conceptually anchored to Du Bois’s Paris pavilion, is without question a more refined solution.

GZ: The lettering at the bottom of the memorial is very brief. Apart from his name, dates of birth and death, and a note on his connection to the university, you describe his ‘profession’ in three words: “Sociologist, Historian, Civil Rights Activist.” I imagine it was very difficult to decide on the exact wording because – apart from these three terms – he was so many things in the different stages of his long life: author of almost erotic novels following the conventions of the chivalric romance, communist, writer of often poetic essays and non-fiction books, Pan-Africanist, founding editor of the prolific Black periodical The Crisis, promotor of the Harlem Renaissance, and more. Was it you and your colleagues, Dorothea, who finally decided on what to write?

DL: Yes, it’s a shame we did not get to mention the eroticism of his novels! It is impossible to describe a person as multifaceted and contradictory as Du Bois with such a limited space. I think his work as a sociologist, historian, and Civil Rights activist had the most profound impact; that’s why we decided on these three “professions.” We hope, though, that Jean-Ulrick’s artwork illuminates other facets of Du Bois’s creativity.

JUD: My conversations with the graphic designer, Detlev Pusch, explored how to use a certain type of lettering/font and format that recognizes the materiality of nineteenth century book-culture and locates Du Bois within the sphere of scholarship, as a man of letters. The butterfly arrangement of the memorial reminds the viewer of holding an open book, with the German text to the left and the English version on the right page of an implied book.

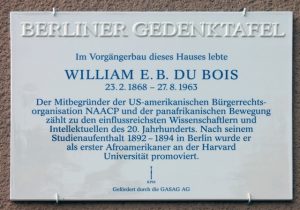

GZ: The lettering also shows that your approach is quite different from the plaque that was installed last year at Oranienstraße 130 in Kreuzberg (fig. 4). It, for example, spells his first name as “William E. B.” whereas you chose the abbreviation “W. E. B.,” and describes his accomplishments in two full sentences. As the Stadtmuseum Berlin has recently started a project on postcolonial remembrance in the city and as controversial monuments linked to white supremacy are currently becoming the subject of mass protests and – in some cases – attacks, it is tempting to think about the memorial in this broader context of public remembrance. Do you intend to position the memorial within this larger project, the project of revealing Germany’s non-white past, of making the presence of Black people and their entanglement with Berlin more visible? More generally speaking, if you think of the students contemplating the memorial in the near future – many of them young white Germans but also some with minority or non-white backgrounds – what, ideally, is the reception you are hoping for?

JUD: When conceiving the memorial commission, I began an online research for as many Du Bois monuments as I could find. I also explored around the main building of the Humboldt University to look at various other commemorative sculptures, plaques, and models, and I attended the unveiling of the public plaque on Oranienstraße. It is a completely different object and context because the house that he lived in no longer exists. The organizers had to mount the plaque on the exterior wall of a new building that is part of the Otto-Suhr-Siedlung, a social housing project built between 1956–1963. But ultimately, the Humboldt University memorial is unconcerned with replicating any of these previous models. It has emerged on its own terms, in the terms described by the historical situation of Du Bois at Humboldt. I don’t see it as taking a strong position against any other plaques or monuments of white scholars that you can see in the vicinity. I think of it as something that is more than a plaque. It has grown into a monument, but, nonetheless, remains a modest monument re-inscribing Du Bois’s humanity, presenting him not as a distant icon but as someone with a real, lived experience that we can be inspired by, and in particular the students, who can personally relate by the virtue of their mutual youth. As regards your question of the presence of the Black or non-white body in European and German spaces, I’m not sure that the memorial is directly able to address this in any manner other than for me to state clearly that even during Du Bois’s initial tenure at Humboldt University there were people of color in the city – though not many – living their lives here in Berlin and contributing to the machine that makes a cultural capital (several decades later even the self-exiled American Josephine Baker would perform in Weimar Berlin and return to the Friedrichstadt-Palast when it was part of the GDR). Beyond that, in any kind of explicit way, I think that’s not the agenda of this kind of monument. You also have to keep in mind that from the different people of color who lived in Germany and contributed to its culture in this period, the experience of Du Bois as an American is probably different from most others, whose multiple roots were somehow connected to the complicated history of European colonialism. My research for other artistic projects on this topic has taught me this.[9] Through it I have begun to understand that the role of the Black body in German history is very complicated and ambivalent, and dates back to unexpected constellations such as the odd status of certain Black people at European courts. This is a history that many people, European and beyond, are completely unaware of because they think about race and racism primarily through the Eurocentric American lens.

DL: We do believe that the memorial will be an important corrective to the plaques and busts of the main building, as it addresses the diversity of the university. We want to recognize both students and scholars of color. Their numbers are far too small compared to the proportion of non-white people living in Germany. Their realities and their knowledges need to become part of academia, they need to be represented in this shared space. The American Studies Program understands its mission as providing a platform for discussion and the exchange of knowledge in the contexts of decolonization, anti-racism, and other movements that fight systems of oppression. I agree with Jean-Ulrick that Germany has deferred racism to the US. This is an interesting aspect of the transatlantic relationship that is not always acknowledged. Du Bois used Germany as a strategic other in order to address race, justice, and social equality in the US; today we can use Du Bois, the Civil Rights Movement, and Black Lives Matter in order to address racism in Germany.

GZ: Dorothea, when we met for our first video conversation, you told me that the current pandemic had slowed the production and installation of the memorial. One and a half months later, the corona pandemic still continues to dominate the global news, but it has received some competition from the “pandemic of racism,” as Benjamin Crump, the attorney for the family of George Floyd, recently described the cause of Floyd’s death. Has this, in any way, changed your prospects? When, and under what circumstances, do you expect to celebrate the opening of the memorial?

DL: The local protests responding to police violence against Black bodies in the US show me that a public discourse is developing in Germany that takes responsibility for Germany’s colonial history and systemic racism. Whether this will speed up completion of the Du Bois memorial remains to be seen. Since we last spoke, our funding has increased by 350 Euros. At this point, everyone involved is struggling with the consequences of either one or the other “pandemic.” The academic team tried to respond to the political situation[10] at the same time as it is managing the mayhem of the digital semester; the artistic team has had to battle both kinds of “pandemics” in various ways. So at this point in time, I cannot possibly say when we can come together to celebrate the unveiling of the memorial! Send me an email and I will let you know when we get there 😉

Gianna Zocco is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie fellow, currently working at the ZfL on her project “Of Awful Connections, East German Primitives, and the New Black Berlin Wall. Germany and German History in African-American Literature.”

[1] Founded in 1809 as “Universität zu Berlin,” today’s “Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin” was named “Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität” from 1810 to 1945.

[2] Although Du Bois recounts in his autobiography how von Treitschke – possibly unaware of the African-American’s presence – elaborated on the “inferiority” of “mulattoes” in a lecture, he describes him as “by far the most interesting of the professors” and “one of the most forcible and independent minds on the faculty.” W. E. B. Du Bois: The Autobiography of W. E. B. Du Bois. A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century. New York: International Publisher 2003 [1968], pp. 164–165.

[3] Ibid., pp. 159–160.

[4] Marianne Hirsch / Leo Spitzer: “The Afterlives of Class Photos. School, Assimilation, Exclusion.” In: Markus Winkler (ed.): Partizipation und Exklusion. Zur Habsburger Prägung von Sprache und Bildung in der Bukowina 1848 – 1918 – 1940. Regensburg: Verlag Friedrich Pustet 2015, pp. 19–40, here p. 22. According to Hirsch and Spitzer, the uniformity characteristic of class photographs such as Du Bois’s can be related to the assimilationist and integrationist ideologies structuring the medium. For this reason, they also describe class photos as “anti-portraits,” arguing that they remain tied to an institutional gaze and therefore tend to negate the uniqueness of the individual subject, which is typically consolidated through the “increase of being” (Hans-Georg Gadamer) produced by portraits (p. 24).

[5] Adolph L. Reed Jr.: W. E. B. Du Bois and American Political Thought. Fabianism and the Color Line. New York / Oxford: Oxford University Press 1997, p. 3.

[6] In the opening paragraph of this speech, Du Bois used the phrase: “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the colour-line,” which became famous when he later reused it in the “Forethought” of The Souls of Black Folk (1903). As Brent Edwards argues, “reading The Souls of Black Folk as an echo to the prior usage at the Pan-African Conference necessitates coming to terms with the ways that the phrase emphatically frames the ‘color line’ not in the U.S. debates and civil rights struggles that are commonly taken to be its arena, but in the much broader sphere of ‘modern civilization’ as a whole.” Brent Edwards: The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 2003, p. 1–2.

[7] A reconstruction of some of the highlights of “The Exhibit of American Negroes” at the World’s Fair in Paris is available online in Eugene F. Provenzo’s “The Exhibit of American Negroes. An Historical and Archival Reconstruction.”

[8] David Levering Lewis: “A Small Nation of People: W. E. B. Du Bois and Black Americans at the Turn of the Twentieth Century.” In: The Library of Congress (ed.): A Small Nation of People. W. E. B. Du Bois & African American Portraits of Progress. New York: Harper Collins 2003, pp. 23–49, here p. 29. This volume also includes about 150 of the circa 500 photographs that were part of the exhibition. They show African-Americans in their homes, churches, businesses, and in community life, and are committed to an agenda of defying the image of Blacks as impoverished, lazy, or uneducated by exemplifying dignity, accomplishment, and progress.

[9] An example for this is Désert’s artwork “Guten Morgen Preußen / Good Morning Prussia”, which is currently on display at the Kunstverein Braunschweig. It is a series of analogue cyanotypes in “Prussian blue”, which narrates the story of the Afro-German band conductor and restaurateur Gustav Albrecht Sabac el Cher (1868–1934), who lived in Berlin at the same time as Du Bois and was “Kapellmeister” of the First Prussian Regiment of Grenadiers in Königsberg.

[10] https://www.angl.hu-berlin.de/news/events/invitation-town-hall-1.pdf

VORGESCHLAGENE ZITIERWEISE: A “Modest Monument” awaiting Completion. Gianna Zocco talks to Jean-Ulrick Désert and Dorothea Löbbermann about the W. E. B. Du Bois Memorial at the Humboldt University of Berlin, in: ZfL BLOG, 16.7.2020, [https://www.zflprojekte.de/zfl-blog/2020/07/16/a-modest-monument-awaiting-completion-gianna-zocco-talks-to-jean-ulrick-desert-and-dorothea-loebbermann-about-the-w-e-b-du-bois-memorial-at-the-humboldt-university/].

DOI: https://doi.org/10.13151/zfl-blog/20200716-01